Research

Social Selection and Polymorphism

Extravagant ornamentation in animals, and it’s presence and absence in nature, has been an enduring fascination of humans throughout history. I study the evolution of ornamentation through the lens of social selection, a powerful framework for elucidating how social interactions and biodiversity interact, potentially leading to evolution of coloration, weaponry, chemical communication, sound production, and more.

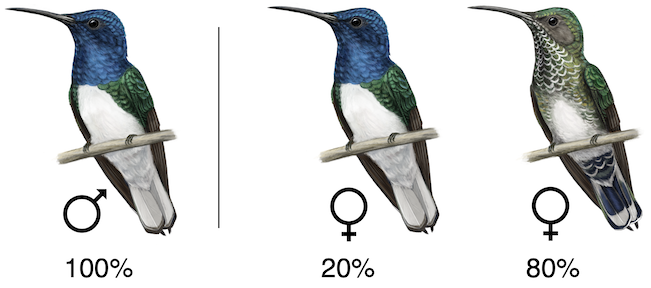

One of the most interesting aspects of social interaction is the evolution of polymorphism, or multiple forms within the same species. I study polymorphism in female hummingbirds, typically the white-necked jacobin (Florisuga mellivora). In this species, males all have brightly colored plumage, but females are polymorphic – some look like males while others have a completely different plumage type. During my PhD, with Dr. Dustin Rubenstein and Dr. Mike Webster, I found that males tend to be more aggressive around nectar resources, and other hummingbirds avoid aggression toward them in order to avoid a dangerous interaction. Females tend to be less aggressive than males on average, but the ones that look like males are able to avoid getting attacked by other hummingbirds because of their resemblance. This allows them to access more nectar resources. Female polymorphism exists in several other hummingbird species, and studying it can tell us a great deal about ornamentation (and it’s absence), competition, and color diversity. (Illustration by Jillian Ditner)

Movement and Energetics

The intake and expenditure of energy is common to all lifeforms. Hummingbirds are unique because they have the highest metabolic rates of all vertebrates, and much of their daily life is centered around finding and consuming flower nectar. Among vertebrates, they also hold records for the fastest speeds compared to their body size, and their wing beat rates far exceed those of other birds. Despite these fascinating aspects of hummingbird movement, it can be very difficult to track their movements due to their small size.

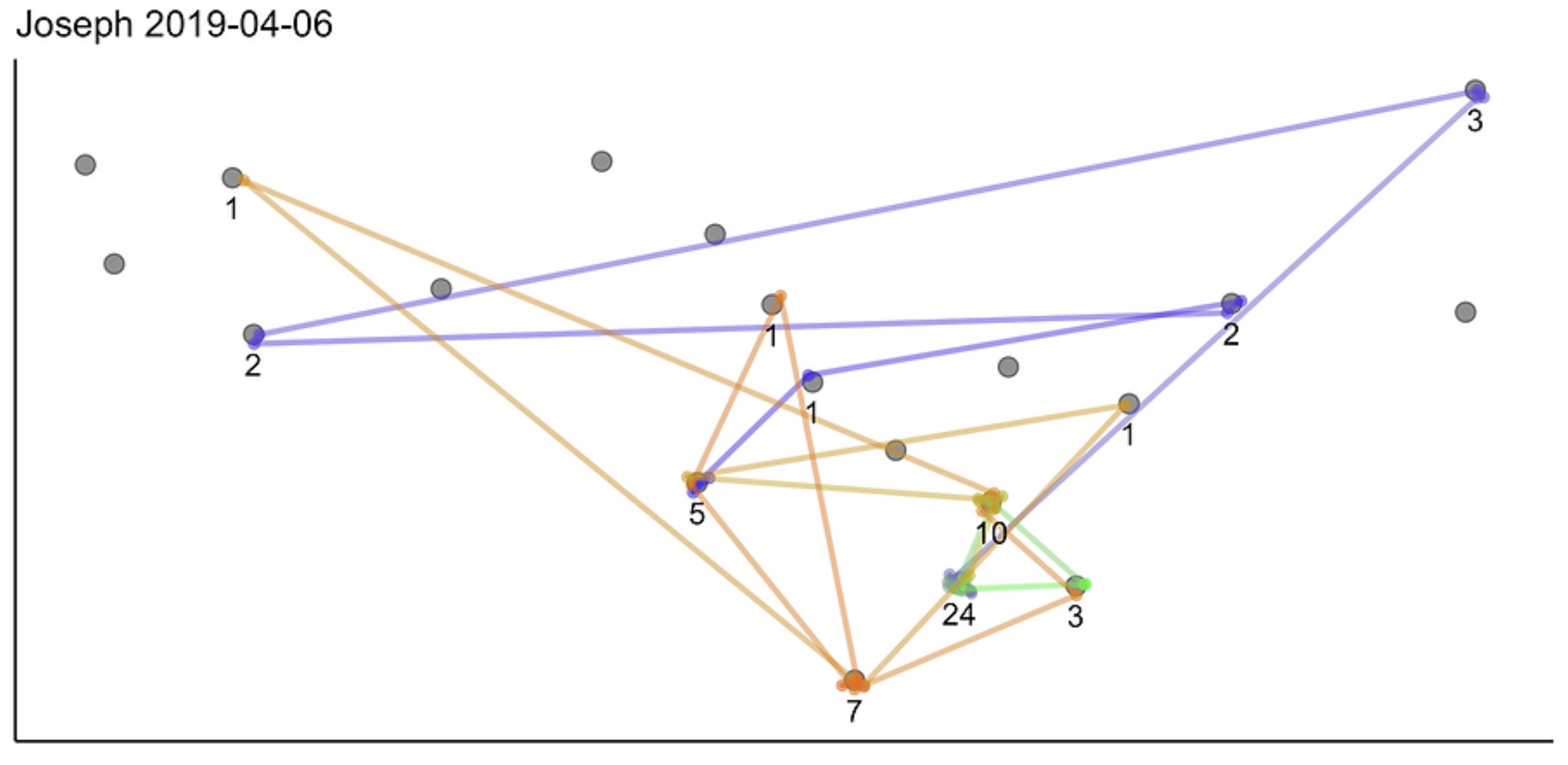

In collaboration with Dr. Alejandro Rico-Guevara (University of Washington and the Burke Museum) we have been developing tools to observe the daily lives of hummingbirds through the use of Radio Frequency Identification (RFID). Birds can be tagged with tiny electronic tags which are then read at a network of feeders equipped with antenna that detect and log the presence of RFID tags. With this dataset, we were able to log over 80,000 feeder visits from over 100 birds. Mapping these data over time and space offers an unprecedented view into the lives of these unique and fascinating animals. Lastly, in collaboration with Dr. Ummat Somjee (University of Texas), we are connecting movement strategy to energetic expenditure through the measurement of metabolic rates, connecting energy intake to output at the limits of vertebrate physiology.

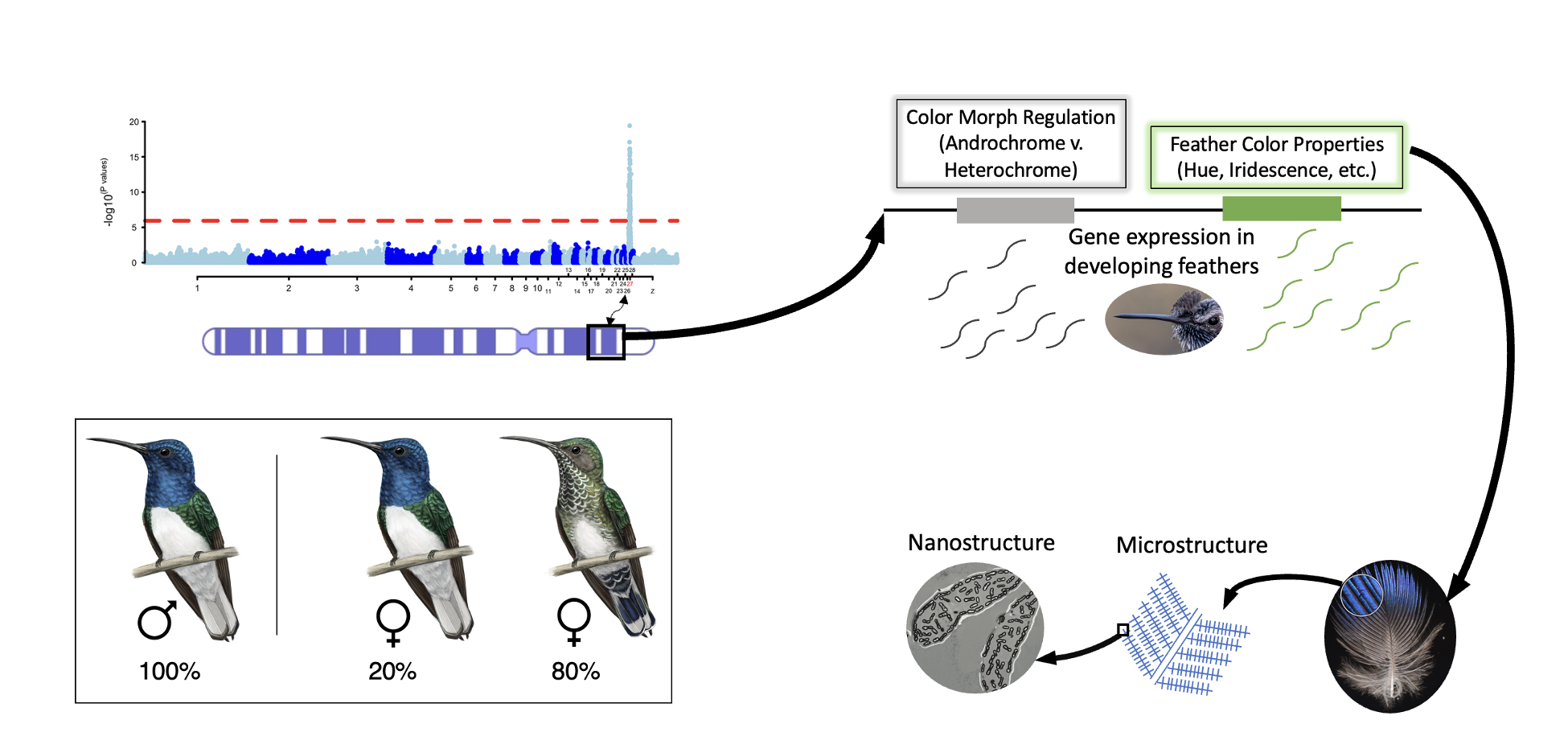

Genetics and Mechanism of Sexual Dichromatism

Sexual dimorphism, when non-reproductive traits differ between males and females, has long been the subject of fascination for both science and society at large. Species vary dramatically in the degree to which females and males differ from each other, representing a major axis of biological diversity. A great deal of attention has been given to the adaptive reasons why sexual dimorphism may or may not evolve, yet surprisingly little is known about how these differences occur at the genomic and developmental level.

In white-necked jacobin hummingbirds (Florisuga mellivora), males and most females have different coloration, yet 20% of females are male-like in coloration and are indistinguishable from males in the field. Importantly, this plumage color diversity in females represents a dimorphic species in which sex and coloration are dissociated, thereby providing a unique opportunity to study the genetic and molecular mechanisms of sexual dimorphism.

Beginning in 2023, I will begin an NSF Postdoctoral Fellowship with Dr. Scott Taylor at CU Boulder and Dr. Owen McMillian at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama to study the mechanistic basis of this polymorphism and to elucidate broad patterns of between-sex variation in this and other animal species